Controversy

follows jury nullification everywhere in criminal law. The power that a jury has to refuse convicting

a defendant, even when the prosecution has provided evidence beyond a

reasonable doubt, understandably does not bode well with many judges and

prosecutors. Jurors have the power to

nullify because courts cannot overturn a not guilty verdict since this would

violate a defendant’s constitutional right to a jury trial.[1] During O.J. Simpson’s trial, discussion of

jury nullification stood at the forefront as Simpson’s defense attorney

encouraged the jury to acquit Simpson even if they found him to be guilty so

the jury could send a message to the Los Angeles Police Department.[2] Nullification has also appeared in cases

where prosecutors charge abused wives for the murder of their abusive husbands, in cases where minors are involved in drug possession or distribution of

narcotics.[3] The question of nullification appeared in

other high profile cases, like the case of former D.C. mayor Marion Barry. Barry was convicted of only one minor count out

of the fourteen charges against him by an African-American jury when he was

caught on tape smoking crack cocaine, even though the trial judge in that case

commented that the prosecutor has a very strong case against him.[4]

New

Hampshire has taken a stance on jury nullification with a 2012 law that

explicitly allows defense attorneys to tell juries about nullification. This law led to more New Hampshire defense attorneys urging juries to acquit in cases where the jury finds the law to be

overly harsh or unfair. Advocates praise New Hampshire’s efforts to

revive nullification as a way to cut down on overly aggressive prosecutors. Critics, like the National District Attorneys

Association Executive Director Scott Burns, consider nullification to be extremely dangerous because it allows juries to circumvent the law which erodes the ability

of laws to guarantee order in society.

Some New

Hampshire criminal defense attorneys argue that the existing law does not go

far enough because it does not require judges to instruct juries on their power

to nullify. By leaving the decision to

instruct on nullification to the discretion of the trial judge, New Hampshire defense attorneys argue that it is much more difficult to include nullification

in an argument for acquittal. A bill introduced this January in the New

Hampshire house would require trial judges to instruct juries that they not

only have the option to acquit when they have reasonable doubt of a defendant’s

guilt, but also when they disagree with the law that indicts a defendant. It is unclear whether the bill will become

law, but this begs the question, how do courts around the country feel about

jury nullification?

In the

1895 Supreme Court decision in Sparf v. United States,

the Court held that federal judges were not required to instruct jurors on

their ability to nullify laws, citing that it would bring confusion into the

administration of criminal law since it would lead to the jury not only being

the trier of facts, but also of law. The

Court held in Sparf that allowing a

jury to make this decision hinders a court’s involvement in matters of law,

leaving these matters to untrained jurors. In the Second Circuit’s decision in United States v. Thomas, the court recognized that

nullification can be a form of civil disobedience and gave the example of

juries acquitting people charged under fugitive slave laws. Additionally, the Thomas court denied that juries reserve the right to nullify

convictions and describes the practice as a violation of a jury’s duty to

follow the law as instructed by the court. However, even though the court in Thomas was critical of jury nullification,

it noted that inquiries on the subject cannot be overly expansive in order to

protect jury secrecy and protect juries from intimidation. Even though the Second Circuit has

reservations about the usefulness and ethics of nullification, it held that

inquiries into whether a juror is engaging in the practice should be

limited. Other courts around the country have prohibited defense attorneys from informing juries of their power to

nullify, circumventing this potential tool for defense attorneys.

New

Hampshire’s move to explicitly include nullification in criminal cases does not

in any way reflect how the rest of the country will treat this controversial

issue in the future. Assuming that the

proposed bill that requires judges to include nullification in jury

instructions does not pass, the current jurisprudence in New Hampshire allows

judicial discretion in these instructions, thereby limiting how many

nullification instructions will reach juries across the state. Without a bill that mandates this instruction,

it is not only up to the judge if nullification instructions reach the jury,

but also up to defense attorneys to decide whether they want to use

nullification as a tool to defend their clients. Critics would argue that the ethical implications

of nullification are too great to allow jury instructions on the subject and

that the rule of law would be eroded if juries decide cases based on their

personal opinions rather than what the law mandates. The Second Circuit in Thomas cited hung juries in lynching cases in the South where white

jurors acquitted white defendants regardless of the evidence presented as an

example of nullification having a real negative effect on the rule of law. Would a zealous defense attorney be unethical

if she decides to use jury nullification as a legal device in her client’s

defense? Advocates, like former federal

prosecutor and George Washington law professor Paul Butler, argue that juries,

especially African-American juries, have the moral duty to acquit defendants if

they find the law is unfair and sending the particular defendant to prison

would ultimately harm the community more than help it.[5]

In a 2011 New York Times Op-Ed article, Butler criticized federal

prosecutors who charged Julian Heicklen, a retired chemistry professor, with

jury tampering for providing information about jury nullification outside the

federal courthouse in Manhattan. Butler explains

that nullification is premised on the idea that ordinary citizens, not

government officials, should decide whether a person should be punished. He states that proponents of the doctrine go as

far back as John Adams and John Hancock.

Following Butler’s logic, defense attorneys who attempt to inform the

jury of their power to nullify are not only properly advocating for their

client, but also leaving justice in the hands of people who are more aware of

what is best for their community, rather than leave the implementation of

justice up to legislators who might not be representative of their community. The

case against Mr. Heicklen for jury tampering was eventually dropped as the judge held that

she would not stretch the interpretation of the jury tampering statute to cover

speech that is not intended to influence the actions of a specific juror in a specific

case.

Regardless

of whether New Hampshire will decide to require its judges to instruct juries

on their power of nullification, the doctrine will remain a controversial topic

in the eyes of many prosecutors, judges, and even some defense attorneys. Last October, a billboard appeared in the Judiciary Square Metro of D.C., where prospective jurors

exited and could see the words “Good jurors nullify bad laws.” This billboard is but one aspect of a growing

national campaign to encourage jurors to acquit defendants when they disagree

with the law. Spear-heading this

campaign is the Fully Informed Jury Association which also lobbied for New

Hampshire’s current jury nullification law and the bill that was introduced

earlier this year. Whether this organization

will be successful in pushing other state legislatures to pass similar laws

that explicitly allow for nullification instructions is unclear, but, if this

is in fact part of a growing national consensus that some laws unduly implement

harsh punishments for “victimless” crimes then we can expect to see more states

following New Hampshire’s guidance.

Practitioners

should be aware of their prospective jurisdictions and how they usually treat

jury nullification. Additionally,

defense attorneys in jurisdictions that are friendly to nullification (or, at

least, not hostile to the practice) like New Hampshire can find themselves in a

difficult situation. In jurisdictions

that allow nullification instructions, defense attorneys would have to balance

the interests of their client and the interests of the community when deciding

to inform the jury of their power to nullify.

In cases of non-violent offenders, defense attorneys have a much easier

time coming to a decision; however, in cases of egregious violent offenders,

this decision can be harder to make. Nevertheless,

by failing to inform the jury of nullification in jurisdictions where the

practice is accepted, defense attorneys might be in violation of their ethical

duty to zealously advocate for their client.

It will be interesting to see whether New Hampshire will pass the bill

that requires judges to inform juries on their power to nullify and the series

of legal and ethical implications that will follow.

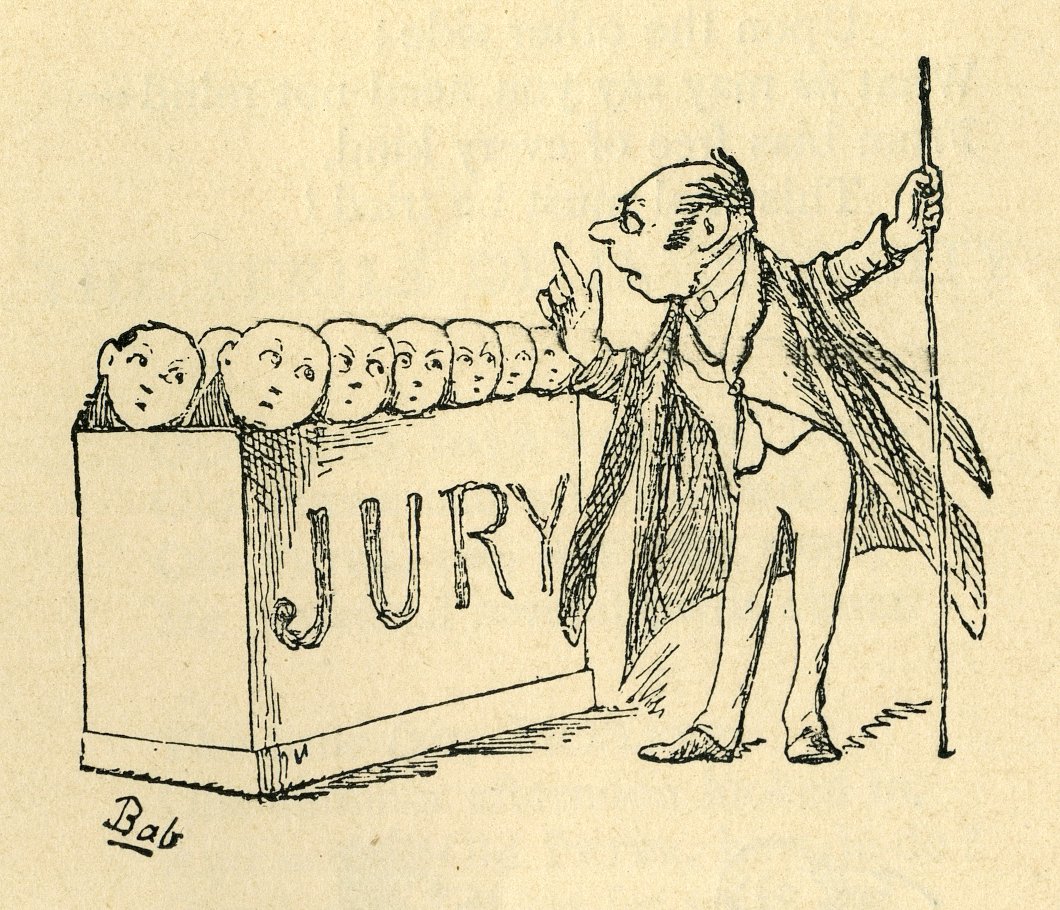

Image by W.S. Gilbert (d. 1911), via Wikimedia Commons.

[1] Stephen A. Saltzburg & Daniel J. Capra, American Criminal Procedure: Cases and Commentary, 1233 (9th ed. 2010).

[2] Id.

[3] Id.

[4] Id.

at 1236.

[5] See

Paul Butler, Racially Jury Nullification: Black Power in the Criminal

Justice System, 105 Yale L.J. 677 (1995).

To answer the question in the title: Why can't it be both?

ReplyDeleteOkay, it can't be both because anarchy requires no rulers, but my point is that anarchy is not necessarily a bad thing. Nobody's arguing it would be a utopia, but it would be a far cry from the dystopia the Powers That Be would have you believe...

The fact that these Powers want to suppress a jury's right to nullify is more than enough to convince me that juries should have that right.