Practitioners

who have handled cases involving marijuana are likely to be familiar with the Duquenois-Levine

field test. As of 2008, the NIK NarcoPouch 908 was the most commonly used marijuana field testing kit utilizing

the Duquenois-Levine Reagent. However, despite its wide use, forensic drug

expert John Kelly stated in a 2008 report to the California Attorneys for

Criminal Justice (CACJ) that there were no published studies examining the

validity of the field test. Kelly’s report, which was written pursuant to one such study, criticizes the

Duquenois-Levine field test as being non-specific and rendering false positives,

which he asserts violate Supreme Court rulings and undermines the integrity of tens of thousands of marijuana convictions.

This is not the only article criticizing the Duquenois-Levine field test. Indeed, a quick Google search shows a few

results among the various outlets where law enforcement officers can purchase the kits. However, most of these

articles are written by Kelly himself. The only other criticisms found were a page

on a criminal defense law firm’s website and a post from a blog about substance abuse. The latter criticism even cites Kelly’s AlterNet article.

While

there isn’t a dearth of criticism on the test itself, some of the criticism

that does exist warrants consideration—namely, a 2012 article in The Open Forensic Science Journal

publishing the findings of the scientific experiments which gave rise to

Kelly’s 2008 report.

The

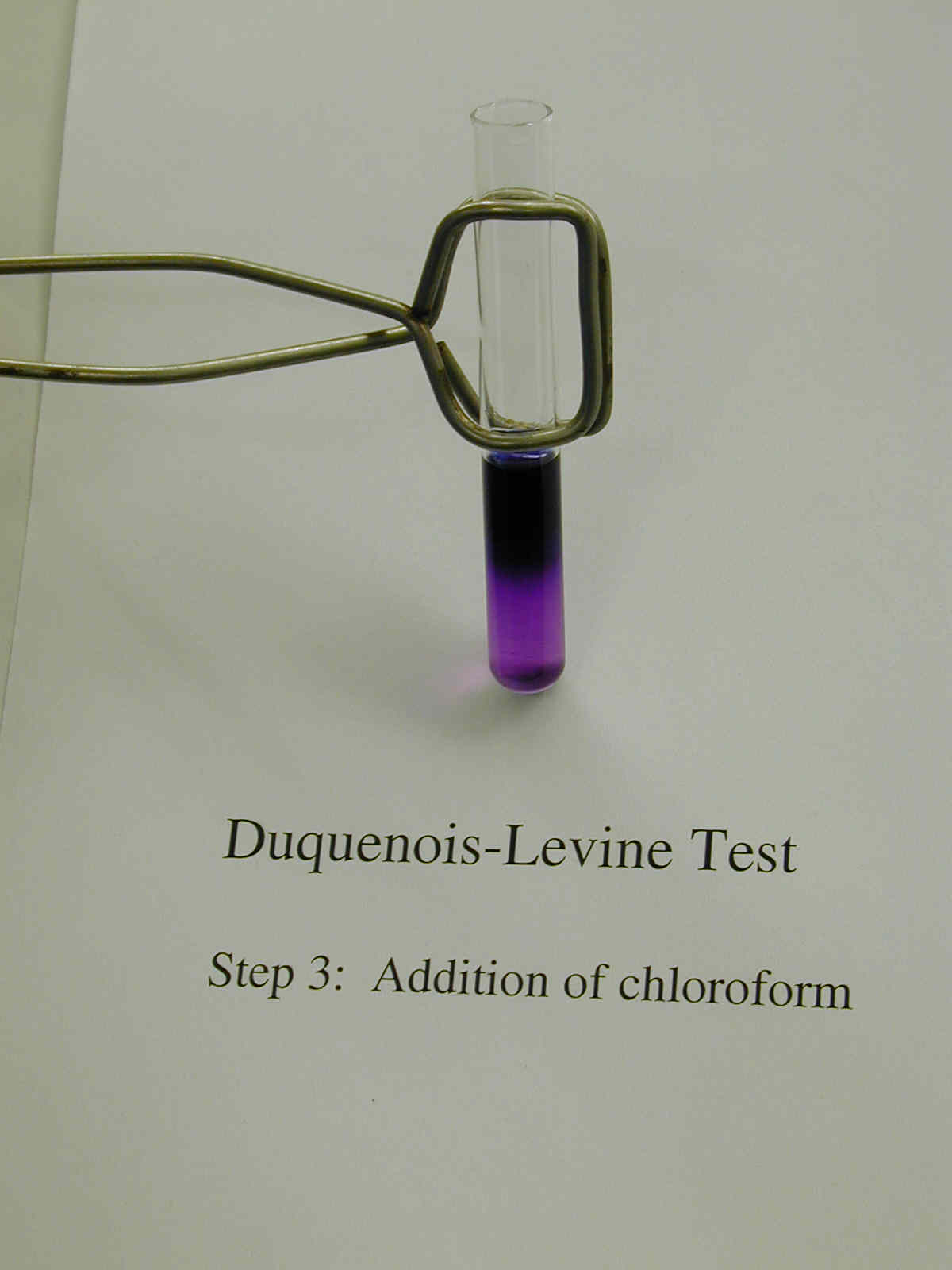

Duquenois-Levine field test is a variation of drug testing techniques that have

been around since the 1930s. The test itself is named after the chemical

reagent used within the field kits that reacts to the presence of cannabinoids,

turning the reagent “an intense violet blue color.” One website which sells the NarcoPouch 908 writes

that the NarcoPouch is “[a] Presumptive Drug Testing [Kit]. . . [which]

consists of hermetically sealed ampoules prefilled with precise amounts of

testing chemicals inside a plastic outer pouch.”

In order

to perform the test, a law enforcement official places small amounts of the suspected

substance into the pouch, breaks the ampoules, and “agitates” the pouch. A positive test will show a reaction in front

of the ampoules. It should be noted that a two page

instruction sheet for the NarcoPouch 908 includes a note written in all capital

letters instructing users to “always retain sufficient sample of suspect material for evidential analysis by the forensic laboratory or toxicologist.” The webpage containing the PDF instructions

also notes that a NarcoPouch only identifies the presence and identity of

controlled substances “with reasonable certainty,” not absolute proof.

In 2012,

John Kelly, along with Dr. Omar Bagasra and Krishna Addanki, two Claflin

University researchers, published “The Non-Specificity of the Duquenois-Levine Field Test for Marijuana” in the Open

Forensic Science Journal, a peer

reviewed Open Access journal published by Bentham Science. The article published the findings from a

2008 experiment which aimed to determine the specificity of the Duquenois-Levine field test in identifying marijuana. These appear to be the findings to which

Kelly referred to in his 2008 CACJ report.

In the

introduction, the article cites a lack of published studies on the specificity

of the Duquenois-Levine field test as one of the primary reasons for running

the experiment, coupling it with the assertion that manufactures, until

recently, claimed that the test can render false positives. The authors additionally provide anecdotal

evidence from a Philadelphia police official and the testing kit’s manufacturer

claiming that the presumptive test kits are 99% reliable. The article also includes anecdotal evidence from

two drug analysts who stated that they had never received a false positive in

thousands of tests.

The

testing itself was performed with NIK NarcoPouch 908 Duquenois-Levine field

testing kits which were used to test non-marijuana substances, such as

chocolate, plant extracts, and medication. After testing forty-two samples, the authors

found that patchouli, cypress, and eucalyptus tested positive while lavender,

spearmint, oregano, and thyme gave inconclusive results. All other non-marijuana substances involved

tested negative.

In their

discussion of the testing and results, the authors immediately noted that they

found the Duquenois-Levine field test to be nonspecific and subjective, arguing

that the positive results for three types of non-marijuana substances indicates

an ability to return false positives. The authors also take issue with what they

perceive to be the inherent subjective nature of the test, arguing that the

“proper blue-violet or purple” color yielding a positive result is different

for each tester, because what is blue or purple enough for one may not be true

for others. From here, the authors argue

that the lack of specificity combined with the potential for false positives,

subjectiveness of the test, and now-disproved statements from law enforcement

officials and drug analysts could jeopardize the integrity of “tens of

thousands” of marijuana convictions.

While

Kelly, Bagasra, and Addanki’s article presents readers with one of the few

direct experiments performed on the Duquenois-Levine field test, one cannot help

but ask how their results may affect criminal cases. While Kelly has written articles for multiple

news outlets to present his arguments for six years, the test results

themselves were not released until just two years ago. Even then, the publication that accepted the

article, The Open Forensic Science Journal is relatively unheard of—there is no impact factor rating listed on two independent websites.

Even

outside of the relative unknown status of the journal, the entirety of Kelly’s

assertions are based upon tests performed on a presumptive field test which, by

its very nature, is not meant to be asserted as conclusive. Kelly even admits to this in his article

published in The Guardian, in which

he states that when the test “turns a certain color—purple, in the case of marijuana—it’s deemed likely to be the real thing.” “Likely” is hardly a conclusory standard.

The field

testing kits presently assert themselves as presumptive tests. A quick glance at five forensic supplier

sites (1, 2, 3, 4, 5) selling three different manufacturers’ Duquenois-Levine field test kits

all credit them as being presumptive. Additionally, as stated before, the

instructions for the NarcoPouch 908, the very product tested in the Open Forensic Science Journal article, remind

users to “always retain sufficient sample of suspect material for evidential analysis by the forensic laboratory or toxicologist” (emphasis added).

There are

very few indications, if any, that Duquenois-Levine field test is meant to

be conclusive in definitively

determining that the substance tested is or is not marijuana. While a positive presumptive test may be used

to assert probable cause in some jurisdictions—Minnesota, for example—it would be careless to rest proof beyond a reasonable doubt on a

positive presumptive field test without a more specific, confirmatory test in

the crime lab. This goes for many field

testing kits, including those for blood, cocaine, and methamphetamines.

While

Kelly’s criticisms of the Duquenois-Levine field test may not have gained

traction within mainstream media, his research has resulted in one of the few scientific studies specifically aimed at addressing the test’s specificity. The results themselves indicate that the

Duquenois-Levine field test may not be as reliable or specific as proponents of

the test once claimed, though the implications may be limited.

The

experiment’s results are perhaps most effective when the defense seeks to

attack the field test’s use to establish probable cause. Given that the test itself is presumptive,

the added level of non-specificity given by the three types of false positives

(patchouli, cypress, and eucalyptus), can be used to attack testing reliability. However, this could be shaky, at best. Unless

someone is in possession of the plant form of these substances, they will

mostly be found in products which are impossible to mistake for marijuana: perfume and beauty products, teas, and wood-based products,

to name a few.

Love this post, and also love Moomin!

ReplyDeleteClick Here:- Criminal defense attorney lawyer boston